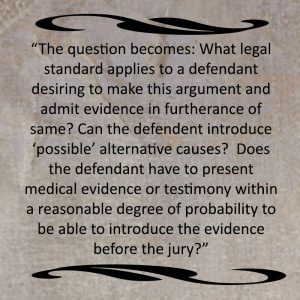

Any attorney who represents clients in cases that require experts will more than likely come across discovery issues involving those experts. Who is considered an expert and whether or not his or her identity must be disclosed? Specifically, what about consulting experts that will not be a witness at trial, must his or her identity be disclosed to the other parties? In cases involving product liability, this is especially common because of the oftentimes-complex nature of the device at issue. So, what about the discovery of the identification of non-witness consulting experts “attending” the examination of the subject defective product? This article seeks to address circumstances whereby the confidential nature of consulting experts might be removed.

For instance, in a product liability claim where expert inspections of the product will take place, do the inspections have to be jointly conducted? Can one party insist upon taking possession of the product and conduct an inspection outside the presence of other parties? If one party and the experts take possession of the product, does that party have to disclose the identity of the expert(s) who will be involved in the inspection and handling of the product, and what will they do at the inspection?

For instance, in a product liability claim where expert inspections of the product will take place, do the inspections have to be jointly conducted? Can one party insist upon taking possession of the product and conduct an inspection outside the presence of other parties? If one party and the experts take possession of the product, does that party have to disclose the identity of the expert(s) who will be involved in the inspection and handling of the product, and what will they do at the inspection?

Alabama Injury Law Blog

Alabama Injury Law Blog